This excerpt is copyrighted material, please do not use or copy without written permission from Nitartha Publications.

This excerpt is from our sourcebook we use for the Mind & Its World IV course. This course is an extensive exposition of the Sautrantika philosophical tradition, based on the expanded version of The Gateway that Reveals the Philosophical Traditions to Fresh Minds root text.

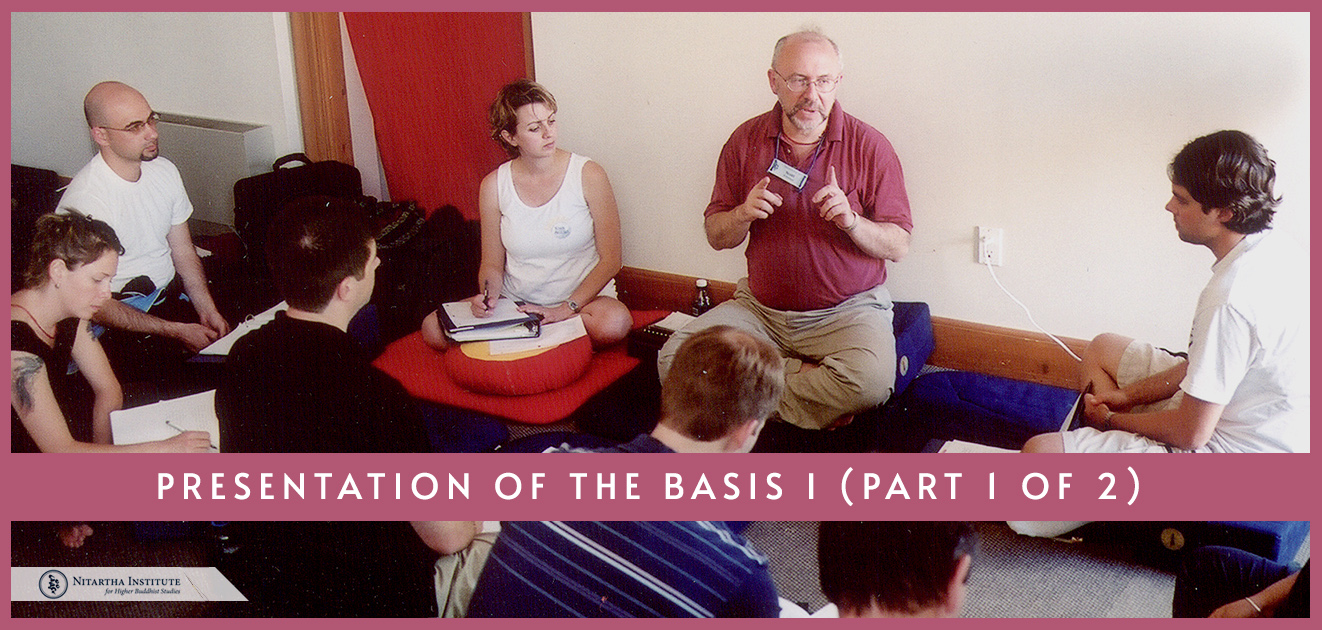

PRESENTATION OF THE BASIS I (Part 1 of 2)

Scott Wallenbach

PRESENTATION OF THE BASIS I

-SCOTT WELLENBACH

Just as with the Vaibhaṣhika system, we will discuss the Sautrantika philosophical system in terms of basis, path, and result. The path and result are essentially the same as in the Vaibhaṣhika system. The bulk of the Gateway text is devoted to discussing the basis or ground because that is where the distinctions lie between the Vaibhaṣhikas and Sautrantikas.

The basis is divided into five parts: objects, subjects, the way consciousness apprehends objects, how to evaluate valid cognition, and their way of asserting outer objects.

OBJECTS

The definition of object is “that which can be known” and the definition of a knowable object is “that which is suitable to be taken as an object of a mind.” Equivalents of object are knowable object, existent, established base, phenomenon, and object of comprehension.

Objects are classified in five ways: the two realities, specifically characterized phenomena and generally characterized phenomena, permanent phenomena and impermanent phenomena, manifest phenomena and hidden phenomena, and the classification in terms of the three times.

TWO REALITIES

The Sautrantikas who follow scripture, which means Vasubandhu’s autocommentary to the Kosha, have the same view as the Vaibhaṣhikas: “If something is destroyed or mentally broken …”

For the Sautrantikas following reasoning, Dharmakirti is quoted: “What is able to ultimately perform a function / Is what ultimately exists. /Everything else is seemingly existent. / These are explained as specifically characterized and generally characterized phenomena,” in other words, ultimately existent and seemingly existent.

Ultimate Reality

The definition of ultimate reality is “A phenomenon that does not depend on imputations through terms and conceptions, but is established from its own side as something that withstands analysis through reasoning.” Ultimate reality is what is there before we label it or even think about it. It does not depend on imputation through terms and conceptions. It is not just physical objects, as we know from our Lorik study. It is also mind. Subjects are also ultimate reality. Thing, specifically characterized phenomenon, what is able to perform a function, impermanent phenomenon, conditioned phenomenon, and ultimate reality are all equivalent. In the system of the Sautrantika, ultimate reality and what is ultimately existent are equivalent.

The next part of the text is interesting: “The explanation of the term ‘ultimate reality’: Specifically characterized phenomena as the subject are called ‘ultimate reality,’ because they are real from the perspective of ultimate minds. Here, an ultimate mind is a consciousness that is unmistaken with respect to its appearing object.” First, in the Sautrantika tradition, all minds—valid cognition and nonvalid cognition, conceptual and nonconceptual, and so on—are specifically characterized, and that is what ultimate is for the Sautrantikas. What is an ultimate mind as opposed to a relative mind? There is no such thing as a relative mind. Second, we need to understand that “ultimate mind” means the mind of an ārya. That is the sense of ultimate here. The last sentence of the paragraph needs to tweaked or removed, because it seems to be talking about an ultimate mind versus a relative mind, and that according to the Kagyu understanding of Sautrantika is just not so.

The definition of ultimate reality is “A phenomenon that does not depend on imputations through terms and conceptions, but is established from its own side as something that withstands analysis through reasoning.” Ultimate reality is what is there before we label it or even think about it. It does not depend on imputation through terms and conceptions.

Student: All minds are ultimate, but only āryas can only perceive things that are real? So we have ultimate minds, but we are not able to perceive anything real?

SW: The text is explaining why the term “ultimate” is used this way. We can perceive what is real. We have direct valid cognition. We may cloud it over and smush it together with concept, but we still have it. It is not saying that only āryas exclusively have direct cognition. It is talking about why we use the word “ultimate.”

Student: How are āryas classified?

SW: They are on the path of seeing and above. Ārya means “noble being.”

Seeming Reality

Seeming reality is defined as “a phenomenon that is established as merely something conceptually imputed.” This is the content of our thoughts, our ideas. Generally characterized phenomenon, permanent phenomenon, unconditioned phenomenon, a phenomenon that is a nonthing, and seeming reality are all equivalents.

The text says: “The explanation of seeming reality: Generally characterized phenomena as the subject are called ‘seeming reality’ because they are real from the perspective of minds within seeming reality.” This line is explaining why they are called a reality at all. Next the text says: “Here, minds within seeming reality are conceptions.” The wording of this line seems problematic. I take the meaning to be that conceptions, or generally characterized phenomena, are the objects of minds in seeming reality. It should probably read: “Here, conceptions (meaning generally characterized phenomena) are the objects of minds within seeming reality.” The last line says: “Since they obscure the direct adoption of specifically characterized phenomena as one’s own apprehended objects, they are called ‘seeming.’ ” As above, the last line of the paragraph I think needs to be recast or removed. We will need to look into this, but for now I think it is fair to say that generally in our experience, what we see, hear, taste, and so forth are conceptualized images. We mix the label and the idea of something with the object. From that point of view, it is the labeling aspect that prevents the direct apprehension of perceptual valid cognition.

The threefold sequence of direct valid cognition, as Ponlop Rinpoche taught in the context of commenting on the Lorik, provides an interesting perspective here: first you have sense direct valid cognition, then you have mental direct valid cognition, which is a registration, and then you have concept. Sense, registration, concept; sense, registration, concept—and the mind keeps speeding up. We miss the mental direct valid cognition altogether, and we mush the sense direct valid cognition and the concept together in our conscious experience. Our train of concept is continually being punctuated by direct valid cognition, but we are going too quickly to catch it. From that point of view, the conceptions that obscure the direct adoption of specifically characterized phenomena as one’s apprehended objects only obscure our conscious attention towards these object, or conscious awareness; actually direct valid cognition is happening all the time.

The definition of a specifically characterized phenomenon is “a phenomenon that is able to ultimately perform a function. The basis for definition is a vase. The definition of a generally characterized phenomenon is “ a phenomenon that is not able to perform a function,” and the basis of definition is unconditioned space.

The text says, “One should understand that, in general, superimposed phenomena, such as phenomena that are one or different, connected or contradictory, or generalities and particulars, are generally characterized phenomena.” Whenever we look at the relationship between phenomena, we are referring to generally characterized phenomena. Specifically characterized are just what they are, and when we start thinking about whether they are singular, different, connected, contradictory, a particular of a generality or the generality that includes particulars, it is our conceptual mind that makes those connections.

CONTINUE…

Read Part II here…