Meditation On Selflessness

This excerpt is copyrighted material, please do not use or copy without written permission from Nitartha Publications.

This excerpt is from our sourcebook we use for Mind & Its World IV class. This course is an extensive exposition of the Sautrantika philosophical tradition, based on the expanded version of The Gateway that Reveals the Philosophical Traditions to Fresh Minds root text.

MEDITATION ON SELFLESSNESS

By ACHARYA KELSANG WANGDI

Personal selflessness can be explained in three contexts:

- the twelve links of dependent origination.

- the four noble truths or the four realities.

- the sixteen aspects of the four realities.

Here, we begin with body and mind.

THE BODY IS NOT THE SELF

The basic examination at the beginning is to examine whether or not the self is the same as, or different from, the five skandhas. The skandhas are here summarized as body and mind for ease of discussion.

The body is not the same as the self because the self is held to be permanent, singular and independent. Fixation on the self gives the impression that the self is a very stable entity. For example, in the perception of self-fixation, the self does not die.

If the self were the body, however, then it would follow that there are many selves since there are many parts of the body. We consider the self to be one thing, not many things.

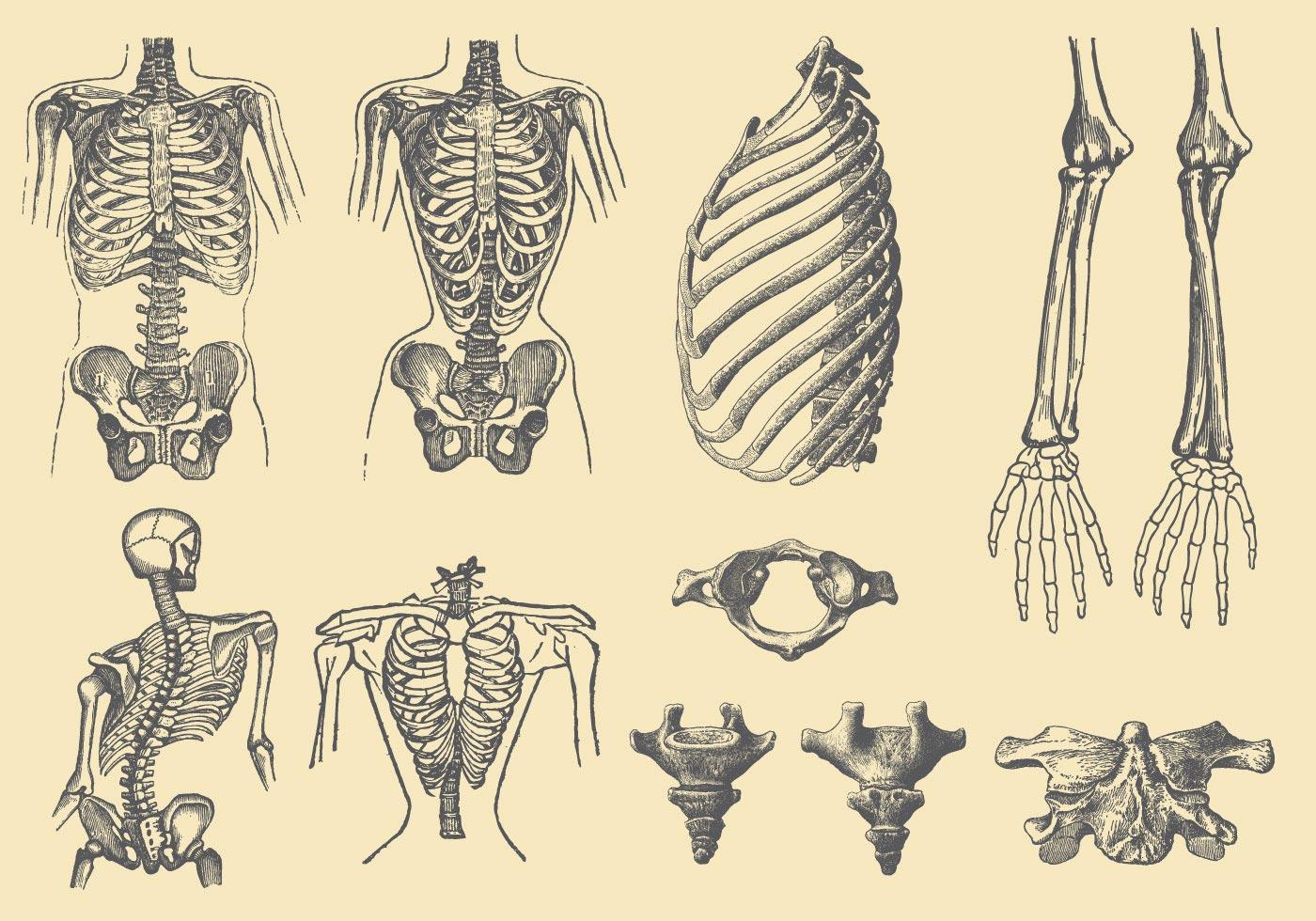

In the Bodhicaryavatara by Shantideva, he examines the body by taking each body part and asking whether or not it is the self. Look at the hair and ask if it is the self; look at the eyes and ask if they are the self; look at the blood and ask if it is the self. So this meditation is a common investigation of selflessness. Personal selflessness is presented in the same way across the board and many detailed investigations are given.

The shravakas, or the hearers, meditate mainly on the personal selflessness of persons rather than the selflessness of phenomena. Their proofs of the selflessness of persons concentrate mainly on the investigation of whether the self is the same as the skandhas or not. They do not investigate the possibility of a self that is separate from the skandhas because that would be a needless analysis, like asking whether there is a self in the horns of a rabbit. If there is no clinging toward it in the first place, then why ask whether there is a self present in there or not?

In the Bodhicaryavatara by Shantideva, he examines the body by taking each body part and asking whether or not it is the self. Look at the hair and ask if it is the self; look at the eyes and ask if they are the self; look at the blood and ask if it is the self.

THE BODY IS NOT THE SELF

The basic examination at the beginning is to examine whether or not the self is the same as, or different from, the five skandhas. The skandhas are here summarized as body and mind for ease of discussion.

The body is not the same as the self because the self is held to be permanent, singular and independent. Fixation on the self gives the impression that the self is a very stable entity. For example, in the perception of self-fixation, the self does not die.

If the self were the body, however, then it would follow that there are many selves since there are many parts of the body. We consider the self to be one thing, not many things.

In the Bodhicaryavatara by Shantideva, he examines the body by taking each body part and asking whether or not it is the self. Look at the hair and ask if it is the self; look at the eyes and ask if they are the self; look at the blood and ask if it is the self. So this meditation is a common investigation of selflessness. Personal selflessness is presented in the same way across the board and many detailed investigations are given.

The shravakas, or the hearers, meditate mainly on the personal selflessness of persons rather than the selflessness of phenomena. Their proofs of the selflessness of persons concentrate mainly on the investigation of whether the self is the same as the skandhas or not. They do not investigate the possibility of a self that is separate from the skandhas because that would be a needless analysis, like asking whether there is a self in the horns of a rabbit. If there is no clinging toward it in the first place, then why ask whether there is a self present in there or not?

THE MIND IS NOT THE SELF

Examine the mind to see whether or not the mind is the self. Start with the six primary minds of the eye, ear, nose, taste, touch, and mind consciousness. Examine in this way until certainty is reached that no self can be found in these. Examine also the forty-six mental events to see if any of them are the self. For example, which mental event of feeling is the self: anger, desire, or prajna?

Analytical Meditation Instructions

First, analyze with thoughts in order to give rise to certainty. Once certainty arrives, let go of thoughts and rest directly within the certainty produced. If we do not let go of thoughts, we would not go beyond this preliminary phase. Our thoughts are like the preliminary phase for developing certainty. Ascertain that the self is not present or does not exist, then rest in equipoise within this nonexistence or absence of the self.

Meditate repeatedly over long periods of time in this certainty. Meditation is gaining familiarity with our certainty.

The bigger picture is easier to see when giving rise to this certainty and resting in equipoise within that certainty for some length of time and in various situations. We have more certainty in the futility of self-fixation. Reflect on how we observe that in which there is no self and yet cling to as a self. Notice this confusion and how we make many mistakes on the basis of this fundamental confusion. Look at how pointless and futile it is to continually foment experiences of mental afflictions because of this clinging.

New insights may arise into our experience of accumulating karma and spinning around in samsara, such as a certainty that there is no real benefit to spinning around in samsara because of ego-clinging or self-fixation.

The experience of self-fixation is vivid in our day-to-day life; it is difficult to overcome the assumptions that the self is permanent, singular and independent. For example, when a headache lasts for a few hours, the clinging to permanence can be found in the thought that the same self is experiencing that headache. The self that experiences the headache at the beginning is assumed to be the same self that experiences the headache at the end. Clinging to a singularity is found in the notion of the self as a single being experiencing the headache, as opposed to just our body or various parts of the body undergoing the pain of the headache.

The clinging to the notion that self is an independent entity is also strong. The basic instruction is to slowly challenge that clinging. Dismantle it in gradual stages through analytical meditation where attention is turned inward, such as the one just described examining body and mind.

Clinging to singularity, permanence, and independence often rears its head in the strongest fashion when we are in physical pain. Pain often causes the mind to have a narrow focus in terms of its experience of phenomena; the pain limits the mind to the experience of phenomena in that region of our body. Although there are many other parts of the body that are not experiencing pain, we focus only on the part of our body that is in pain. This is an expression of clinging toward a singularity. Mind wants to fixate on this single experience and not consider any other factors in the present moment. It is not willing to acknowledge the multiplicity of our experience when that pain is arising. By allowing attention to include a focus on the bodily parts that are not in pain in addition to the ones that are in pain, the experience of that pain would be a much more open, spacious, and relaxed experience. The pain itself might even be reduced with a wider perception.

There is a type of pain therapy where the patient concentrates on a part of the body that is not in a state of pain. The patient acknowledges that there is no pain present there then moves to a different part of the body and acknowledging that there is no present there either. This is a wonderful meditation that is quite harmonious with the meditation on selflessness. We can meditate in the same way.

If you are curious about this class, learn more here.